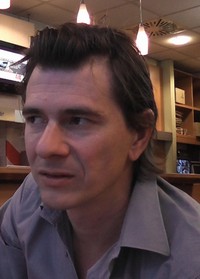

Interview: Dimitri Verhulst – October 2012 - second part

Írta: ekultura.hu | 2012. 10. 19.

Dimitri Verhulst spent a couple of days in Budapest as the guest of the Department of Dutch Studies at Eötvös Loránd University.

We met him for a long conversation on his last day here. We talked about his books published in Hungarian by Europa Publishing House, about alcoholism, about love - and many more topics.

Due to the length of the interview we publish it in two parts.

ekultura.hu: Would you tell me about your relationship with your readers?

Dimitri Verhulst: I don`t know them. Once in a year I sign books on a book fair in Antwerp where we have a huge book fair for Dutch-written books, and there I can meet some of my readers, at least those who are asking for a signature. Because not all readers, fortunately (laughs), ask for a signature in a book – I never do it, for example. But I don`t know them, my readers. Sometimes they write letters but not all of them. Some of them are young, some of them are old. I don`t know them. I really don`t. And I`m glad that I don`t know it. So the only one I`m writing for, at least when I`m writing, it`s me. I am the one who has to say it`s a good book. And then I leave it up to the others. I think it`s a boring answer because all writers would say the same.

ekultura.hu: No it`s not. There are writers who write blogs, post on Facebook, Twitter...

Dimitri Verhulst: I`m not on Facebook for example. So I don`t have to count my friends. (laughs). I don`t write a blog. I`m afraid I have to say I`m old-fashioned in literature. For me a book still is a book. I don`t even have an e-reader.

ekultura.hu: And would you mind if your novels were available for e-readers?

Dimitri Verhulst: They are available on e-reader. It`s good that they do exist on e-readers. Life continues, there`s nothing wrong with it. You know an the beginning of the personal computer there were many writers who said: I will never write with a personal computer. But it`s ridiculous, it`s great to write with a personal computer.

ekultura.hu: We had a Swedish author here last year who said he still writes his books on a typewriter.

Dimitri Verhulst: It`s a choice. I know at least one writer in the Dutch region who is forced now by his editor to use a personal computer because they don`t have the personnel anymore in the publishing house to retype all the stuff on a computer or to scan it. But Márquez for example, said that refusing a personal computer and saying that a pen is the best thing to write books with is something like a farmer who would refuse using a tractor and keep on using his horse. It`s personal of course.

ekultura.hu: But if he`s successful this way and everyone reads him then it`s the writer`s choice how he writes.

Dimitri Verhulst: Of course. When you`re feeling yourself better with your pen then you have to write with your pen. But as long as there`s literature on an e-reader, it`s about literature. Whether it`s printed on paper or not, it`s literature. I can live with it very much. On the other hand you see some funny things when you compare literature with music. You have iTunes, you have mp3s and everyone said, well, compact disks very soon will disappear, and the reaction was even funnier. They all started buying vinyls again, these old vinyls, there are strange things going on I think, and maybe we will have this with books as well. And somehow I hope that the e-reader will force the makers of books to make our books more nice, to edit them nicely, to have good concurrency with the e-readers because I adore books, I really adore books but they have to be edited in a nice way, in a nice cover, with good print, a nice touch, everything. If we have good books, people still will keep on buying books. I`m very convinced about that.

And you may not forget the factor of snobbism. If you have a library in your home with all your books you can say as a good snob: I have read all these good books. (laughs) With an e-reader you don`t have this kind of communication. When you visit a friend for the first time you start watching his books, and say: „oh, you like that one too” and you have a conversation about literature or about music. With an e-reader or Ipod you don`t have these kind of conversations. You don`t see the intellectual baggage, it`s hidden. So I believe we will still, for a long time, keep on having our intellectual baggage – music, literature in a material way. And I do hope, for sentimental reasons, but I do hope.

ekultura.hu: How much pressure do you feel about having your novels liked by the readers and the critics as well?

Dimitri Verhulst: I would like to say that I don’t feel no pressure at all but I do. Because I am in a luxury position, I can live from my books. And I know I had been working before, I had been working in factories, I had done some silly jobs like, I`d been pizza delivery boy, things like this, and writing after my job – I did this. And there’s nothing wrong with that, on the contrary, it’s very good that a writer know what it is to work. A writer should know what life is, what real life is. So I’m very thankful that I’ve been through this. But I know now that I’m a better writer now that I can do it full-time. My concentration is 100% so it would be a pain in the *ss if I had to return back to the factories or the pizza delivery period of my life. So, I hope my books sell well, that the critics are good so I can keep on writing because that’s the thing I always wanted to do and now that I have it in my hands I don’t want to lose it again. So there’s a certain kind of pressure of course.

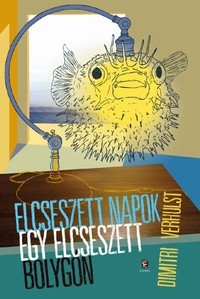

ekultura.hu: You won the prestigious Libris Prize with this novel (Goddamn Days on a Goddamn Globe). What was your reaction? In general, how important is it to you to have your work rewarded with prizes?

Dimitri Verhulst: Well unfortunately we live in a culture where books don’t have a long lifetime and books have to fight to get attention. I don’t like being on television for example. I’ve been asked to do all kinds of silly things on television, participating in a quiz, or singing, or dancing. You cannot imagine the stupid things I’ve been asked for on television – I refuse this. I want to be on television to talk about literature or about society if I have something to say about society. So, if you’re not on television it’s hard to defend your work. The only way to defend it is winning a prize. Because even our literature magazines are so thin, they are thinner, thinner, thinner. The quality of the reviews is not anymore what it was twenty years ago. We see much more interviews because that’s easy for the journalist, interviewing someone. That’s also why some editors don’t publish anymore some writers because that writer, he cannot give an interview anymore. It’s a very bad situation for literature nowadays. So that’s why the pressure is always there and why, unfortunately, it is important to win a prize, because this prize you say, it has some prestige. It really has, it has because you earn 50000 euros with it and that’s a lot of money, it’s really a lot of money. You give it all away to the taxes, but it’s a lot of money. But you have to know who is in the jury – this is only the prize of 5 people being in the jury. If you put 5 other people in that jury someone else would have won the prize, without any doubt. So it’s very relative of course and I can live with the theory that a prize like this is very relative. But it’s important, it’s very important. Absolutely important. When you go to Frankfurt where they sell the rights, the translation rights for all over the world, ---- the publishers look for those who won the prizes. Who won the Booker Prize. We all know that Julian Barnes won the Booker Prize – but who were the other five writers on the list who could have won the Booker Prize – we don’t know. But they wrote five, I suppose very well-written books – so, you see it’s important. It’s important for lazy editors, these prizes. And for lazy readers. And it’s important for those who want to buy a book as a gift with Christmas – they are looking at the top5 list and say that will be good I take that one. That’s how it works. And, well, my name is not J. K. Rowling (laughs). As you see how much the publishers everywhere in the world have paid to buy the rights for J. K. Rowling and what this means for other writers, because they don’t have the money any more to invest the money they put in J. K. Rowling, to invest this money in young, talented writers whom no-one knows, and that’s a pity. Because we have to defend the future of literature and look to the young writers or the older writers no-one knows with lots of talent. And well, the forgotten ones. But it’s – well, it’s a marketing thing, literature. It’s someone that has to be sold.

ekultura.hu: You are a rather prolific writer. How do you manage this with time and strength?

Dimitri Verhulst: I’m not out of discipline. I like the writing so much that automatically in the morning, after breakfast I go to my table and it’s really that way, I’m still fond of writing. I don’t know why. As I told you in the beginning of the interview I don’t know why I love writing but I keep on loving writing.

ekultura.hu: How do you decide when there’s a place for some swear words in your books?

Dimitri Verhulst: Sometimes it has to do with the language, the Dutch language, the rhythm of it. For sure this is getting lost in translation, but I do understand this of course. Nasty words, well, they’re only useful when they have an effect. When you’re using 50 nasty words on one page, well, for boys of 16-years-old maybe it could be funny but not for an adult anymore. So it`s when they have an effect, when my words are as strongs as bullets or when they need to be as strong as bullet, then I prefer using the nasty words. But what’s nasty? There are so many nasty words nowadays everywhere. I think more than ever literature has become a place where nasty words have a function. Because in all movies, on T-shirts, everywhere you have the nasty words so it’s like sex. I don’t write, I don’t like writing about sex. We’ve been through this and there’s no taboo anymore to fight. And I want literature to be that place where you discover new themes and new taboos.

ekultura.hu: We cannot but wonder at your succinct, pointed sentences. How much time does it take to write these?

Dimitri Verhulst: I write a lot but I write slowly. Most of the time I’m just sitting at my table and working on a sentence and rewriting it. And at the end of the day I have 400 words, or something like that. It’s not a lot. When I’ve written 800 words I have a great day, then I say: wow, I’ve been working hard today, I wrote 800 words. It’s very difficult to tell this to someone who is working in a factory, who is building houses or is a postman. But 800 words for me, that’s a hard day, it’s a hard day’s labour. So that’s how fast I work. But not all my sentences are the same, sometimes it’s falling in my head, it’s falling on my paper, and you say: wow, god – he exists (laughs). And sometimes it’s the product of long and difficult thinking. It depends. I have my days of glory and my days of work like everyone. And all jobs I think have this difference between good days and bad days.

ekultura.hu: Do you consider yourself a Belgian or a European writer?

Dimitri Verhulst: I don’t have a nationality. I don’t have it. Of course when I’m going to Singapore I know that I’m in another culture than mine, they have other habits, the code of living together is different, of course all these things I notice but I prefer living in a world without the idea of nationalities. So I’m not thinking about this when I’m writing – where am I from? I never ask myself these kind of questions.

ekultura.hu: And do you feel at home everywhere in the world?

Dimitri Verhulst: No, no, no. I think I could live in Budapest for example. Because when you’re travelling you always ask yourself this question, at least I do: could I live here? I think I could. But there are places in the world where I would be very unhappy. Denmark, for example. I don’t like being in Denmark. I don’t know why but I become very sad there. But I could not live everywhere. I’m not so cosmopolitan that I could live everywhere, I’m afraid. I would be very sad in Siberia, I suppose. Poor Pussy Riot to have to be there for two years now. No, I couldn’t. But I don’t consider myself as a Belgian or a European, that’s the other part of the answer.

ekultura.hu: How many hours do you usually write a day?

Dimitri Verhulst: Four. That’s, I think is an average. Four. So that’s a half-time job but it’s impossible, really impossible to write eight hours a day, you cannot do this, I never met someone who wrote eight hours a day. I would like to, I really would like but I’m tired after four hours.

ekultura.hu: And do you write everyday?

Dimitri Verhulst: Almost everyday. And it’s not a punishment, it’s really not. I do it, but I don’t force myself. I haven’t been writing in Budapest now, I didn’t. But what is writing? Of course, walking through Budapest and observing might be writing for me. Maybe the thinking is much more important than the fact of writing it down.

ekultura.hu: Is writing an addiction for you?

Dimitri Verhulst: I would miss it. I don’t know what I would do without it – I would probably start playing music.

ekultura.hu: So you must be a talent then.

Dimitri Verhulst: In writing? Well, maybe, maybe, a little bit, yes. Yeah of course somehow there will be something of a talent. One part will be the talent, a gift from nature – thank you, Nature. And the other is working. We always have the impression that it’s easy to work with something when you’re talented but... An old friend of mine has a talented voice, a unique baritone. He was born it, really a gift from nature. You cannot provoke having a baritone – you have it or you don’t have it. But he loves the chello. So he’s been singing in a choir when he was young because he loved the music of Bach and singing the Magnificatas as a boy. But he loved the chello. And everyone, all his teachers in the conservatoire are saying, you have a unique baritone, you know it, we were looking for your voice for 70 years, you should be an opera-singer. And he doesn’t like it. He wants to play the chello, don’t wanna f*cking sing in the operas, he doesn’t like it at all. So in his mind because he adores music, classical music, he feels himself responsible for the music: so if I was given this voice or when I’m responsible for music I have to sing. But he can’t. He can’t because his love is not at the opera. His love is at the chello. So, he’s playing chello, in an awful way (laughs), he’s not the great Rostropovich for example, he never will be, but it’s a choice. He has chosen the thing he’s loving and not for the talent. So it doesn’t always fit – the love and the talent.

ekultura.hu: But in your case it seems to fit.

Dimitri Verhulst: Well, it’s not so modest when I say that I’m talented so I prefer when you say it. (laughs) When you say it, it fits together then.

ekultura.hu: And what do you do when you’re not writing?

Dimitri Verhulst: Reading. (laughs) Well, what everyone is doing – cooking, going to the groceries, buying potatoes and cleaning my jeans and cleaning the house and making coffee and drinking coffee – yeah, what everyone is doing. I feed the animals and work a little bit in the garden, and I’m lucky I have a little bush, I adore working with trees and preparing the wood for the next winter, so these are things I like very much and I do ride the bicycle a lot, that’s something I do. You can consider this as a Belgian, well, disease, riding bikes. It’s a tradition, yeah. Here you see lots of race bikes in Budapest, I’m astonished how many bikes you’re seeing, you see much more race bikes in the city than you do in Belgium. I was wondering why you don’t have a cycling champion when everyone is riding racing bikes here. And in Belgium you could earn a lot of money with these bikes because this is an older type, they’re in the museum in Belgium. We have all the modern bikes.

ekultura.hu: And what about football? Have you ever considered writing a football-novel?

Dimitri Verhulst: I’m not talented at all. But I’m a supporter of a football team. As a soft supporter.

ekultura.hu: And are you planning to write a novel about football?

Dimitri Verhulst: I did, I did. One. It’s translated into German, for a German magazine they translated it. It’s an essay about being a football supporter. It’s only translated into German – a nation of football lovers, of course, Germany. They always win. (laughs)

ekultura.hu: And also England and Spain...

Dimitri Verhulst: Yeah, of course. And once Hungary, once in the 50s. We never were, but at least once Hungary was a football nation.

ekultura.hu: And do you plan to write some more about it – football?

Dimitri Verhulst: No, no, no. I wrote an essay for the fun of it, because I do like sports, I’m not that intellectual, high-brow writer who finds sports something for the poor and stupid, not at all. But I’ve written already about it, so...

ekultura.hu: Could you tell me something about the reader-writer meetup on Thursday? How did it go?

Dimitri Verhulst: I heard the two critics very known and feared in Hungary, they told me that, well, most of the times they don’t like books but they were very positive about mine. One of them said that he’s been thinking about founding a club for atheists and that he wanted my book (Goddamn Days on a Goddamn Globe) to be his bible so that’s an honour, a big honour. And also, there were people in the shop who came listening – so, that’s unbelievable. When you have a presentation of your book in another country and people want to go to it and listen – it’s remarkable. It was nice, really. And it was nice at the university, too. I gave a kind of lecture about my literature for students who are studying Dutch literature. And I was so astonished about their level, they are speaking Dutch so well, really high level students – great. You must have a good university to reach that level, frankly.

ekultura.hu: What are your plans for the future?

Dimitri Verhulst: I finished a novel, which means that the manuscript is finished. And I’ve been talking with my editor about the manuscript and now I have the period when I don’t write. I try to forget that I wrote a book, so that’s why I’m here now and not writing. I use this period for making some promotion for translations and after one month I turn back to my manuscript and I read it again and I hope that I might be able to read my own work as a reader. Which is impossible, but I try to read it with fresh eyes and then I have to make corrections, and give my benediction and publish it.

ekultura.hu: Are your books edited by your publisher’s?

Dimitri Verhulst: I don’t support an editor. I would like to have the feeling that I am the one who wrote the book. So I don’t want someone to say: that’s not good, I would rewrite this, I would do that. But I accept the second opinion of an editor. And I like the confrontation and his criticism, because he’s the first one against whom I have to defend my manuscript. And I like the confrontation very much but I don’t want him to rewrite my book. But of course now I’m in a very good position to do this. It’s my fourteenth or fifteenth book now in Dutch, and the publisher, he knows, well, he will sell some of them. I have a certain known name now in our literature. But it’s another thing to do when it’s your debut. When it’s your first book you dare not say it to an editor: don’t touch my writing. I can do it now of course, it’s easy to do, when my editor doesn’t agree I can say, well, okay, I’m going to another publishing house (laughs) – I can afford myself this kind of arrogance.

ekultura.hu: Did this ever happen?

Dimitri Verhulst: No, no. I’m very thankful for my publisher. I sent the manuscript of my first book in the 90s to seven publishers and he was the only one who wanted it. And he did invest four or five years in my books, they didn’t sell at all, well, very little. He kept on believing that I was a good writer. And when I had my first bestseller, the other publishers came: „hey, come with us, you’re welcome” and then I said, no, thank you, I wasn’t welcome in the beginning, I’ll stay loyal to the one who believed in me when no-one wanted me. So I’m still with my first publisher. And it’s very important to give this signal to the next generation because I want to stay loyal to a publisher who believes in a writer who doesn’t have immediately that much success. We are too much in a culture of bestsellers. It’s not because you have a bestseller that you have a good book. You have to keep on publishing the other ones, too. So it’s no hard thing for me to do, staying with the same publisher.

ekultura.hu: My last question: do you believe in love?

Dimitri Verhulst: Of course! Yes! Of course. Of course you asked two words which are hard to explain – believing and love. What is love and what is believing? But I do believe in love, and I can prove it because when there is no love in my life I’m unhappy, I don’t function anymore. There’s constantly the need for love, it’s a kind of, well, drug, it’s food, it’s water, it’s a lot. I believe in love. Long live love!

ekultura.hu: Do you think that every needs to find their true love, their only love in life?

Dimitri Verhulst: Well, sometimes love stops and then it doesn’t have to continue. We have to accept that it might stop, but the worth, the value of that – I can take it as it was and be happy with the love there once was and accept that it stopped. I have no problems with that.

ekultura.hu: Do you believe that you have to find the person, the only person with whom you are one, united?

Dimitri Verhulst: Well, if you want to find something, you may not search. When you start looking, you won’t find it.

ekultura.hu: You are very lucky then – being lucky in your professional and private life.

Dimitri Verhulst: Yeah, but it takes some efforts of course, I mean, I was with someone else when I found my wife, and I had a child, so I had to divorce and so on. You have to do something, you have to say: there is the one. You never know it for sure. You always take a risk but you have to do something, you have to leave, you have to leave a family, you have to accept that everyone’s saying „he has left his wife and he’s a father”. Or you still keep on sitting on your sofa and accepting your average life with television and your own house and... Yeah, sometimes you have to take a risk.

ekultura.hu: Thank you very much for the interview.

Dimitri Verhulst: It was my pleasure.