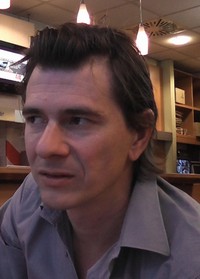

Interview: Dimitri Verhulst – October 2012

Írta: ekultura.hu | 2012. 10. 18.

Dimitri Verhulst spent a couple of days in Budapest as the guest of the Department of Dutch Studies at Eötvös Loránd University. We met him for a long conversation on his last day here. We talked about his books published in Hungarian by Europa Publishing House, about alcoholism, about love - and many more topics. Due to the length of the interview we publish it in two parts.

ekultura.hu: When did you start writing?

Dimitri Verhulst: Difficult question...well it`s not a difficult question but the question of course is when did I start writing in a literature-way. I`ve always been writing, telling stories as a child. You have many children who make drawings and they colour pictures and in one way or the other everyone, or lots of children are busy with something arty. I was the one making stories. I bought little empty books and told some Jules Verne-like stories and illustrated them.

ekultura.hu: So you read a lot?

Dimitri Verhulst: No, I never read. Reading, as a child, it was something for, well, for girls. (laughs) I didn`t like reading at all and I didn`t grow up in a „cultured” family. So we didn`t have books at all at home. We did not have music at home. We had a little radio. So I didn`t grow up in a culturally correct family. Reading, I discovered at the age of fourteen. So I skipped the child literature.

ekultura.hu: And how did you become a writer?

Dimitri Verhulst: No idea. No idea – because it was something I liked, telling these stories, writing them down particularly. I don`t know why I liked this but I liked it. The fact of being alone, at a table, with a pen, being alone with the story and telling it – I adored it. But why I adored it I don`t know, I can`t tell you. I think you must be a psychiatrist or something to know this.

ekultura.hu: So basically there was no author who inspired you? Maybe later on?

Dimitri Verhulst: There are, there are. Absolutely. Later on. But there were not in the beginning of my career as a story-telling human being.

ekultura.hu: And who were they?

Dimitri Verhulst: Well, some of them are of course Dutch-speaking, I suppose you won`t know them. Louis Paul Boon is one of them. The other one is Jeroen Brouwers. It`s not a shame if you don`t know them of course, we are in Hungary and they are particularly known in the Dutch-speaking region. But as well as other ones like the Frenchman Louis-Ferdinand Céline, or Márquez who, I think is a more than remarkable author. We don`t live in ancient times anymore, we can read authors from all over the world now. I don`t believe in something as a national literary culture. For example Murakami is read all over the world nowadays, which means that also in Budapest, young writers are growing up with his literature and not by definition with the literature from Hungary nowadays. So it`s becoming more and more...globalized and I have nothing against it, at all.

ekultura.hu: And who are your favourite authors? Are they the same?

Dimitri Verhulst: Yes, more or less they are the same. I think I have to say that those who inspired me are my favourites. Of course I do discover authors nowadays I didn`t know when I was very much influenceable in my style. For example, to mention a Hungarian one, Sandor Marai is much known today in Europe. They discovered him now as he was abandoned and was forgotten in literature for a long time. So that`s someone we can discover today. And I like him very much. He is really someone I can like, I can adore, but he didn`t influence my style, because, well, more or less my style, I suppose is formed for 70% or something. I hope it still will develop but the main thing will be there, I suppose.

ekultura.hu: When do you decide whether you put your empathic or critical self to the foreground when you are writing?

Dimitri Verhulst: Well, the empathy and the critical point of view, I suppose they go together. You need empathy to get into the mind of a character, you always need it as a writer, at least that`s my opinion, and it`s sharpening your critical side when you have empathy. I don`t believe in a war between empathy or emotion and on the other hand criticism or intellectualism. They match together very well.

ekultura.hu: According to certain critics the style and world-view manifested in your books resemble the style and world-view of Kurt Vonnegut. What do you think about this comparison?

Dimitri Verhulst: Kurt Vonnegut, the American one. I haven`t read enough Kurt Vonnegut to say whether it`s true or not.

ekultura.hu: I mean there are comparisons because of the black humour.

Dimitri Verhulst: It`s possible. It`s absolutely true that I like black humour. That`s a fact. I can`t deny it.

ekultura.hu: If I`m not mistaken, you write poetry, and also work as a journalist besides writing novels. In which genre do you most feel at home and why?

Dimitri Verhulst: The novels. Without any doubt. I only wrote one album with poetry, long ago. 11 years ago it was published. I still write poems now and then but the problem with poetry is that no-one is reading it, well, well, almost no-one is reading it. And it`s very hard to sell and to publish poetry. But that`s not why I wouldn`t publish it. When you believe what you write is a good poem you should publish it even without being sure it will find ten readers. When it`s good it`s good. Period. But I`m getting very sad from writing poems. It`s a hard thing to do. And I don`t smoke anymore, and I want to smoke when I write poems. It`s hard for me, writing poems. And when do you publish them? How many poems do you need to have an album, to have a book of poetry? These are decisions which are hard for me to make, personally, so I write poems now and then, but they are strictly personal and I keep them for my own. And the novel is...I`m afraid I have to tell you that the novel is the kind of stuff I like very much.

ekultura.hu: Of course you are a very successful novelist, so this is a really great choice.

Dimitri Verhulst: Well, accidentally. I didn`t choose it because it`s today. Because in the 18th century of course poetry was much more popular than it is today. But it`s really accidental. I suppose I still would have written novels when they weren`t popular at all. I think my talents are there. Now and then I write theatre, I really like it, the theatre, because working with the dialogues is a very funny thing to do, and I like to give my characters a voice of their own. So I do write theatre, but in the end I`m always a happy man when I start a new novel – it`s like I`m going on holiday...

ekultura.hu: Your breakthrough to the general public came with Problemski Hotel. How did you react to the success of this book?

Dimitri Verhulst: I was very happy and I wondered at the same time because it was my international breakthrough. It wasn`t a breakthrough in my own country. It didn`t sell so well in Belgium. It was the other countries in Europe and even outside Europe, like Argentina for example that they liked the book. I got good reviews there and they bought the rights to translate it. So I was astonished because suddenly there was an interest in my work from all over the world, without the book being a success in my own language. A very strange thing to notice. But of course I was so happy and so proud because I believe in literature as a form of art bringing people together, showing that human beings have lots in common, that Japanese, Rumanian, Swedish, French – we all have the same, or could have the same emotions, the same taboos. I believe in a kind of universal humanism. For example, I gave you the example of Murakami, it`s not that I`m a fan of Murakami, not at all. But I know that in Europe lots of younger people adore his work, which is a funny thing to notice because he`s coming from Japan and sometimes he`s writing typical things out of contemporary Japanese culture. When this is touching people in Europe this means that we have, as human beings, something in common. And therefore I find it very useful that literature is getting translated. Could you imagine what a sadness it would be if Kafka wasn`t translated? Everyone understands what Kafka wants to say, the fact of being alone, of being lost in administration. It`s something universal. So therefore I`m so grateful that my books now might be things that help understand people from everywhere over the world that we have some funny things in common.

ekultura.hu: Several readers claim that the protagonist resembles the South African photojournalist, Kevin Carter. Are they right in this assumption?

Dimitri Verhulst: The reason why I took a photographer is because I was in the asylum-seekers` centre for research. And I felt like a tourist. Because I was there together with people who had to fear for their lives. Because when they are turned back to, for example, Pakistan, if they vote for the wrong party, or if they have the wrong religion, they know very well that they are going to be killed. It`s very hard reality. And I`m there for research and I go out with stories, their stories and I`m making a book with it. And, well, I`m earning my living with it, with their stories, with their misery. I don`t like to write about writers because there are too many books about writers, I even don`t like to read them. But I wanted an alternative for that point of view, the stranger who is watching in an artistic way and who feels guilty about this. Because I felt guilty, being there and using their stories. It didn`t feel too honest in a way. So that`s why I took the point of view of the photographer.

ekultura.hu: In The Misfortunates you write about your family and childhood with shattering honesty and bitter cynicism. And if I`m right, you covered autobiographical topics in several other books as well. Do you not regret anything you ever put on paper?

Dimitri Verhulst: Yes of course. Yes. I do. For example I took a risk with using some true names, it`s always a risk. And you`re always losing friends, after each book I have fewer friends. I know a writer who says after each book I`m losing a wife. (laughs) Yes, of course, sometimes I do regret the choices I made but I`m afraid it`s part of the game. If I had taken another choice maybe I would regret that choice, too. But sometimes I do regret choices, yes, absolutely.

ekultura.hu: But on the other hand maybe you gain other friends, instead of the lost ones.

Dimitri Verhulst: Oh, yes. When you`re writing and you`re writing in an honest way, you`re always using stuff you find around you, in your personal life. I cannot write about your personal life because I don`t know your personal life. I can imagine it. But when I`m imagining your personal life, I`m using things I`m seeing in mine. I will transfer it to yours but I`m always using my thoughts and my surroundings. I have no other choice. Otherwise it would be complete invention, and I`m not a writer of the pure invention.

ekultura.hu: And do you have other events in your childhood you would like to write down?

Dimitri Verhulst: I do. For example I have been in a home for abandoned children between 14 and 18. That`s the period after The Misfortunates. And it`s quite original because there are very few people who have been in it. Who in Belgium is an abandoned child? Those who have no parents and no family, and little criminals – they were all put together in a home. And one day I would like to write about this but I`m not ready for it. I`m ready in my mind, but I`m not ready as a writer. I wait with that book until the day that I consider myself a good writer. Because I don`t want to write that book two times. I have to write it immediately in a way of which I know that this is a good book. So hopefully my style is getting better and better, and when my style is at its best I will write that book.

ekultura.hu: Your style is always changing.

Dimitri Verhulst: I hope, I hope it`s developing.

ekultura.hu: So it`s a neverending development.

Dimitri Verhulst: You always take a risk, because I might die. I often hear people saying, writers particularly that a writer is at his best between his 50s and his 60s. We have an example now of a German writer, Siegfried Lenz. I don`t know if you know him or not. He is from the same generation as Günter Grass, same age. He is less known but now he is writing books at the age of 80-something. And they are so good! So you think, when you`re fearing your old days, and you think: „oh, at the age of 80 what will I be writing if I don`t have Alzheimer`s at least” – you can think there is hope that it`s possible to write very astonishing good books at the age of 80. So, I have hope.

ekultura.hu: And when will you start writing about your present life and what will you write?

Dimitri Verhulst: I am too happy now. (laughs)

ekultura.hu: So there`s nothing to write about?

Dimitri Verhulst: Nothing interesting. But I have been writing about happiness, of being happily married. Because it`s...well, it`s a breaking point. They say you cannot write about happiness, because everyone is saying it`s hard to do, to write about happiness and love. I saw this as a challenge. (laughs) And I wrote about it. It`s something in-between poetry and a novel, but it`s not translated.

ekultura.hu: Do you consider alcoholism such a serious problem?

Dimitri Verhulst: I do. I do. I have noticed that, at least in Belgium, when we are talking about alcoholism the theme is considered as something Émile Zola would write about, something from the past: well, we don`t have this problem, not so much nowadays, it`s something „vintage” and from the past. But it`s not, of course. I believe as a modern civilization you have to say that it`s a problem when children grow up in families where there is alcoholism because you`re playing with these children`s future. I was shocked when we were already in the 21st century, when 11 o`clock at night I was riding home on my bike and I passed a café and I saw a child sleeping on a billiard table in the bar. And I knew this image very well because I had been a child sleeping on a billiard table at night while my father was drinking. So there hasn`t changed a thing in those 25 years. Our nation and how we manage alcoholism didn`t develop in all those days. We do have a law in Belgium saying that it`s forbidden for children to enter a bar if they are less than 18 years old, it`s very good that we have a law like this. But this law doesn`t say a thing about how the parents should be in that bar, how`s their status – are they drunk or not. When you`re a mum or dad, or drunk, the child is welcome in the bar because he is with his parents, so this is a problem of course. And I see it when I`m walking through Budapest, it`s a f*cking problem, lots of people drink too much. And these people you see drinking on the street, and some of them will have children. What are we going to do with their future? Do we want them to find a job, to have some diplomas, to go to university? If you want the next generation of Hungary to be well-educated then we have to take care of them now. I was lucky. I had a judge who said, well, we have to take you out of this situation and I was placed in a home and a host family. I could escape out from that sad situation. Because in 99% of these cases you will see that you do inherit alcohol problems. It`s hard to say but it`s reality and you have to do something about it. And when I was saying that literature has the power to show human beings that we have lots of things in common and that there`s something like a universal humanism, well, that`s what I heard yesterday, some people said about The Misfortunates that this could be a Hungarian book. I heard the same in Japan, too – this could be a Japanese book, they said. Which means we have this sad problem everywhere in the world.

ekultura.hu: How does it feel to you to re-read your earlier works?

Dimitri Verhulst: I don`t like it. I really don`t like it. Sometimes I have to do it, for example now because it`s translated, and then you have to return to your books. The Misfortunates I wrote in 2004, published in 2006. So I have to return now to a book I wrote almost ten years ago. Which means that I have to go back to the style that, I hope is less better than it is nowadays and I have to return back to the young man I was (laughs)... the younger man I was when I wrote this book. And you always see the mistakes. Of course you must be able to say: now the book is finished and accept that there will be mistakes in it you will discover in about ten years. So we are now these ten years later.

ekultura.hu: Do you correct these mistakes when there`s a new edition published?

Dimitri Verhulst: No, it`s not that kind of mistakes. It has nothing to do with that kind of mistakes, it`s more a mistake of choices, stylistics things, more like that. And I see The Misfortunates as the book I wrote when I was 32 years old and it always will stay that book, and I still have so many things to tell, I want to tell that I don`t want to rewrite The Misfortunates in my life. I don`t want to do this. I could do this of course. You have painters who always repaint the same thing. Someone like Mondrian, always painting the same painting, making it better and better, but he stayed with the same idea. For me that`s patchwork, it`s almost patchwork, intellectual patchwork. I don`t like it at all.

ekultura.hu: What is your opinion about the film version of The Misfortunates?

Dimitri Verhulst: It`s not a bad one at all. There are worse adaptations of books. And I can accept the film as a film. There are some changes in it but of course they had to change something. I believe it`s a good adaptation. I didn`t like the music in it, it has some thriller effects sometimes. Okay, I can live very much with the movie.

ekultura.hu: How much influence did you have in matters concerning the screenplay?

Dimitri Verhulst: A lot, but I didn`t want to. I was asked to work together on the screenplay. They even asked me to write the script for the film but that would have been a stupid thing to do because I wrote the book as I wanted to write it and it was finished for me. I had it in the form I wanted it at that time and it would have been for the first time in my life I wrote a script for a movie, I never did that before. So, leave the movie to the professionals I would say. I know something about writing books but not about films, it`s another job, I guess. So I gave them carte blanche, they could do what they wanted, it was their film.

ekultura.hu: Does it often happen that a Belgian film becomes a success in France as well?

Dimitri Verhulst: Yes it does. Very much. And there`s the French-speaking part in Belgium. We have the brothers Dardenne, maybe you know them, they won some Golden Palms, they are very good. We have Benoît Poelvoorde, he`s a good actor. We have a very good Belgian cinema, really very good. But that`s the French-speaking films. They are starting to be well-known all over the world. And very often they are talking about, well, social themes and are humorous. The Walloon humour is not bad at all, very much better than the Flemish humour. The Flemish humour is not so good in my opinion. In the French-speaking part of Belgium the jokes are better. That`s why I live in the French-speaking part. (laughs) That was a bad joke maybe.

ekultura.hu: In the novel Godverdomse dagen op een godverdomse bol (Goddamn Days on a Goddamn Globe) you write about mankind with an almost unbearably bitter sarcasm. Do you really think that our situation on this earth is this bad?

Dimitri Verhulst: Of course. (laughs) Yes. Well, we`re living so close to the edge, really very close. But we have a choice. We can amuse ourselves and create some fin-de-siecle spirit, or Titanic – singing while we are sinking – that`s an option. Maybe it`s a good one. Or we can do something about it. But we`re living very close to the edge. As you have seen in Fukushima, as you have seen in Chernobyl. The world is full of Fukushimas and Chernobyls. We have three of them only in Belgium. Even Europe, it`s full of potential Fukushimas and Chernobyls. I`m only talking about nuclear stuff because with that we can be ruined immediately. We are too many people. We are far too many. It`s unbelievable how many children we are making. We are too many – and there`s not enough. Were less people on the earth there would be much more amusement and place for us to amuse ourselves in. We would have more food. And all these things are very much known. I`m saying nothing new at all. So yes, it`s bad. Humankind – we`re living on the edge. Absolutely. We do. And I`m telling the story, the history of mankind as if mankind was a character. To be honest I thought this book already did exist. I`ve been living with the idea for this book for years, and I thought I cannot write because it probably does exist already. But it did not. Now I`m scared of the day someone says, hey, it did exist (laughs).

I`ve been studying for it. I had to re-study history for this book. Because I wanted the facts to be correct, otherwise it wouldn`t have made sense to write something like this. And that`s what you notice: in our history we have always been inventing great stuff, it`s really fabulous, we are geniuses, not all of us of course, but some of us and we do and invent smart things, but we never think... In chess a good chess player is making a movement but he`s making his movement because he knows that the next three movements will be okay for him. That`s what we are not doing with our inventions. For example, nuclear energy or the atomic bomb or whatever, all these kinds of inventions we are making without thinking about or calculating the consequences. And we know we are bad. We know we are bastards and one day or another someone will be abusing good inventions. We know it.

ekultura.hu: Do you think we know it that we are bad?

Dimitri Verhulst: Yes...I know I`m bad.

ekultura.hu: But I think most people who make these problems, they don`t think they`re bad.

Dimitri Verhulst: Do you think so? Brrrr. We are not bad... (laughs) And the other story of course I wanted to tell about this book is that I am an atheist and I have the impression that I have to defend my atheism. I can be offended as an atheist all the time, everyday. But there`s no law against it. When a religious person is offended, it`s a catastrophe. And I`m always wondering, and I`ve always been and I`m afraid I will do this till the end of my days that the power of religion is so strong still nowadays that we keep on making wars, that we keep on killing for god. I do respect people who are religious, I haven`t said the opposite, but I`m wondering that we still keep on killing and killing and killing and killing for a god, whether he`s existing or not, a god who`s saying that we have to be good with each other. Still nowadays, in 2012 and this is what you see through all the history. It`s so constantly the same shit all the time. And it`s repeating itself, repeating itself, repeating itself. We are not getting smarter in that point. It makes me angry, yes, it`s making me angry. Of course it makes me angry.

ekultura.hu: So this is why you`re writing novels?

Dimitri Verhulst: Exactly. And it`s why I wrote this one.

ekultura.hu: Do you consider yourself an observer from the planet Mars, or just a human being with strong opinions?

Dimitri Verhulst: I`m from here. I`m from here and the difference is that if I was from Mars I would see human beings or society as a bad thing which is there. Now I have to tell myself, as I said before, I`m bad, too. I`m the same. Me too. I have my mistakes, and I`m the same person as...as Hitler. I`m the same animal. We all are. And I have to take care of myself all the time because I know somehow, somewhere deep in us we must have the same...what is it? I don`t know what it is but somewhere we have the same things as all those monsters from history.

ekultura.hu: But it`s a difference that you know all these things, and other people don`t.

Dimitri Verhulst: Yes, but it`s good to have the point of view from the earth and not from Mars.

ekultura.hu: Your novel is 163 pages long in the Hungarian edition. Did you originally plan the book to be this short?

Dimitri Verhulst: Well I wanted to have a certain speed. It had to be fast, as it`s going fast, life is going fast and our history is going fast. I wanted it to be fast. And I would lose this effect if I had novel of 800 pages. Even a novel of 35 thousand pages would be a short one when we are talking about our history. So I wanted to be short and of course it`s a European history, so I had to make some decisions. For example the invention of printing books already did exist in China before it existed in Europe, but for me it`s the 15th century, the books. I know there already were books. So you`re making choices and that was one choice, the European point of view. It had to be a neutral point of view but that`s hard in translation. We have a word like the English „it”. It`s not a man and it`s not a woman, but a word like this you don`t have in Hungarian so I think here it`s something like the „hero”, the protagonist is something like „our hero” in Hungarian. In Dutch, in my language it`s „het” so I didn`t have to make the choice between man and wife, it`s quite neutral. And I had to skip some things. Like Napoleon, for example, he`s not in it at all. But it was a choice, yeah, to have it short.